Last week we concluded our 3-part introductory series to the zip function. In the first episode we saw that zip goes well beyond the function that is defined in the Swift standard library, and in fact it generalizes the notion of map that we are familiar with on arrays. At the end of the episode we provided some exercises to help viewers dive a little deeper into what zip had to offer, and this week we solve most of those problems!

Exercise 1 In this episode we came across closures of the form

{ ($0, $1.0, $1.1) }a few times in order to unpack a tuple of the form(A, (B, C))to(A, B, C). Create a few overloaded functions namedunpackto automate this.

This function can be handy for juggling nested tuples, and it’s straightforward to define the first few overloads:

func unpack<A, B, C>(_ tuple: (A, (B, C))) -> (A, B, C) {

(tuple.0, tuple.1.0, tuple.1.1)

}

func unpack<A, B, C, D>(

_ tuple: (A, (B, (C, D)))

) -> (A, B, C, D) {

(tuple.0, tuple.1.0, tuple.1.1.0, tuple.1.1.1)

}

func unpack<A, B, C, D, E>(

_ tuple: (A, (B, (C, (D, E))))

) -> (A, B, C, D, E) {

(tuple.0, tuple.1.0, tuple.1.1.0, tuple.1.1.1.0 tuple.1.1.1.1)

}

This function makes it easier to unpack nested zips. For example, higher-order zip can now be defined quite succinctly:

func zip3<A, B, C>(

_ xs: [A], _ ys: [B], _ zs: [C]

) -> [(A, B, C)] {

zip(xs, ys, zs).map(unpack)

}

func zip4<A, B, C, D>(

_ xs: [A], _ ys: [B], _ zs: [C], _ ws: [D]

) -> [(A, B, C, D)] {

zip(xs, ys, zs, ws).map(unpack)

}

Exercise 2 Do you think

zip2can be seen as a kind of associative infix operator? For example, is it true thatzip(xs, zip(ys, zs)) == zip(zip(xs, ys), zs)? If it’s not strictly true, can you define an equivalence between them?

Unfortunately zip cannot be made into an associative infix operator because the resulting type from zip(xs, zip(ys, zs)) is (A, (B, C)), whereas from zip(zip(xs, ys), zs) it is ((A, B), C). You can of course define a repack helper that transforms between those nested tuple types, but it’s just not strictly true that zip is associative.

Exercise 3 Define

unzip2on arrays, which does the opposite ofzip2: ([(A, B)]) -> ([A], [B]). Can you think of any applications of this function?

The most straightforward way to define unzip is to simply do two maps that each project onto a component of the tuple:

func unzip2(_ pairs: [(A, B)]) -> ([A], [B]) {

(pairs.map { $0.0 }, pairs.map { $0.1 })

}

However, this is looping over the array twice, which isn’t necessary. To avoid that we can instead use a mutable variable:

func unzip2(_ pairs: [(A, B)]) -> ([A], [B]) {

var xs: [A] = []

var ys: [B] = []

for (a, b) in pairs {

xs.append(a)

ys.append(b)

}

return (xs, ys)

}

Exercise 4 It turns out, that unlike the

mapfunction,zip2is not uniquely defined. A single type can have multiple, completely differentzip2functions. Can you find anotherzip2on arrays that is different from the one we defined? How does it differ from ourzip2and how could it be useful?

What if instead of iterating over both arrays simultaneously to pair off their elements, we paired each element of the second array with each element of the first array? Essentially, creating an array of all possible combinations of pairs from both arrays. The implementation might look something like this:

func combos2<A, B>(_ xs: [A], _ ys: [B]) -> [(A, B)] {

var result: [(A, B)] = []

for x in xs {

for y in ys {

result.append((x, y))

}

}

return result

}

combos2([1, 2], ["one", "two"])

// [(1, "one"), (1, "two"), (2, "one"), (2, "two")]

That implementation certainly does the trick, but it’s not super functional. Lots of statements instead of expressions, and lots of mutation. We can simplify things by using map and flatMap on arrays:

func combos2<A, B>(_ xs: [A], _ ys: [B]) -> [(A, B)] {

xs.flatMap { x in

ys.map { y in (x, y) }

}

}

combos2([1, 2], ["one", "two"])

// [(1, "one"), (1, "two"), (2, "one"), (2, "two")]

Much simpler and succinct!

However, it still is strange that there seem to be two completely different implementations of the function signature ([A], [B]) -> [(A, B)]. We will explore this idea more in future Point-Free episodes.

Exercise 5 Define

zip2on the result type:(Result<A, E>, Result<B, E>) -> Result<(A, B), E>Is there more than one possible implementation? Also define

zip3,zip2(with:)andzip3(with:).Is there anything that seems wrong or “off” about your implementation? If so, it will be improved in the next episode 😃.

We ended up solving this in part 2 of our zip series. To implement zip on results you must switch over two result values, and then handle the four cases. Three of those cases are straightforward to implement, and in fact there is only one possible implementation. The last case, however, has two possible implementations, and both throw away some information, which seems not ideal:

func zip2<A, B, E>(

_ a: Result<A, E>, _ b: Result<B, E>

) -> Result<(A, B), E> {

switch (a, b) {

case let (.success(a), .success(b)):

return .success((a, b))

case let (.success, .failure(e)):

return .failure(e)

case let (.failure(e), .success):

return .failure(e)

case let (.failure(e1), .failure(e2)):

// Two possible implementations...

return .failure(e1)

return .failure(e2)

}

}

Take note that in the last case we have no choise but to either discard the e1 error or the e2 error. Watch part 2 of our zip series to understand more in depth why this is not ideal, and to see how a whole new type that is closely related to Result solves this problem very neatly.

Exercise 6 In previous episodes we’ve considered the type that simply wraps a function, and let’s define it as

struct Func<R, A> { let apply: (R) -> A }. Show that this type supports azip2function on theAtype parameter. Also definezip3,zip2(with:)andzip3(with:).

We also ended up solving this in part 2 of our zip series. We came up with the following solution:

func zip2<A, B, R>(

_ r2a: Func<R, A>, _ r2b: Func<R, B>

) -> Func<R, (A, B)> {

Func<R, (A, B)> { r in

(r2a.apply(r), r2b.apply(r))

}

}

This allows us to zip two functions together as long as their input types are the same. In the episode we explored this idea a bit more and showed how it unlocks some interesting expressivity when dealing with lazy values.

Exercise 7 The nested type

[A]? = Optional<Array<A>>is composed of two containers, each of which has their ownzip2function. Can you definezip2on this nested container that somehow involves each of thezip2s on the container types?

Dealing with nested types can be quite confusing because of the layers, so a trick to simplify a bit is to define a typealias for the nested type:

typealias OptionalArray<A> = [A]?

Now that we only have one type name to deal with, OptionalArray, we can very easily state what its zip signature should look like:

func zip2<A, B>(

_ a: OptionalArray<A>, _ b: OptionalArray<B>

) -> OptionalArray<(A, B)> {

fatalError()

}

And how might we implement this? Well, the outer layer, Optional, has a zip operation for transforming a tuple of optionals into an optional tuple, so let’s start there:

func zip2<A, B>(

_ a: OptionalArray<A>, _ b: OptionalArray<B>

) -> OptionalArray<(A, B)> {

zip2(a, b) //: ([A], [B])?

fatalError()

}

Now we have an optional tuple of arrays. We want to apply zip to the tuple of arrays, but it’s trapped in an optional now. Well, never fear, our old friend map can safely open up that optional:

func zip2<A, B>(

_ a: OptionalArray<A>, _ b: OptionalArray<B>

) -> OptionalArray<(A, B)> {

zip2(a, b).map { zip2($0, $1) } //: [(A, B)]?

fatalError()

}

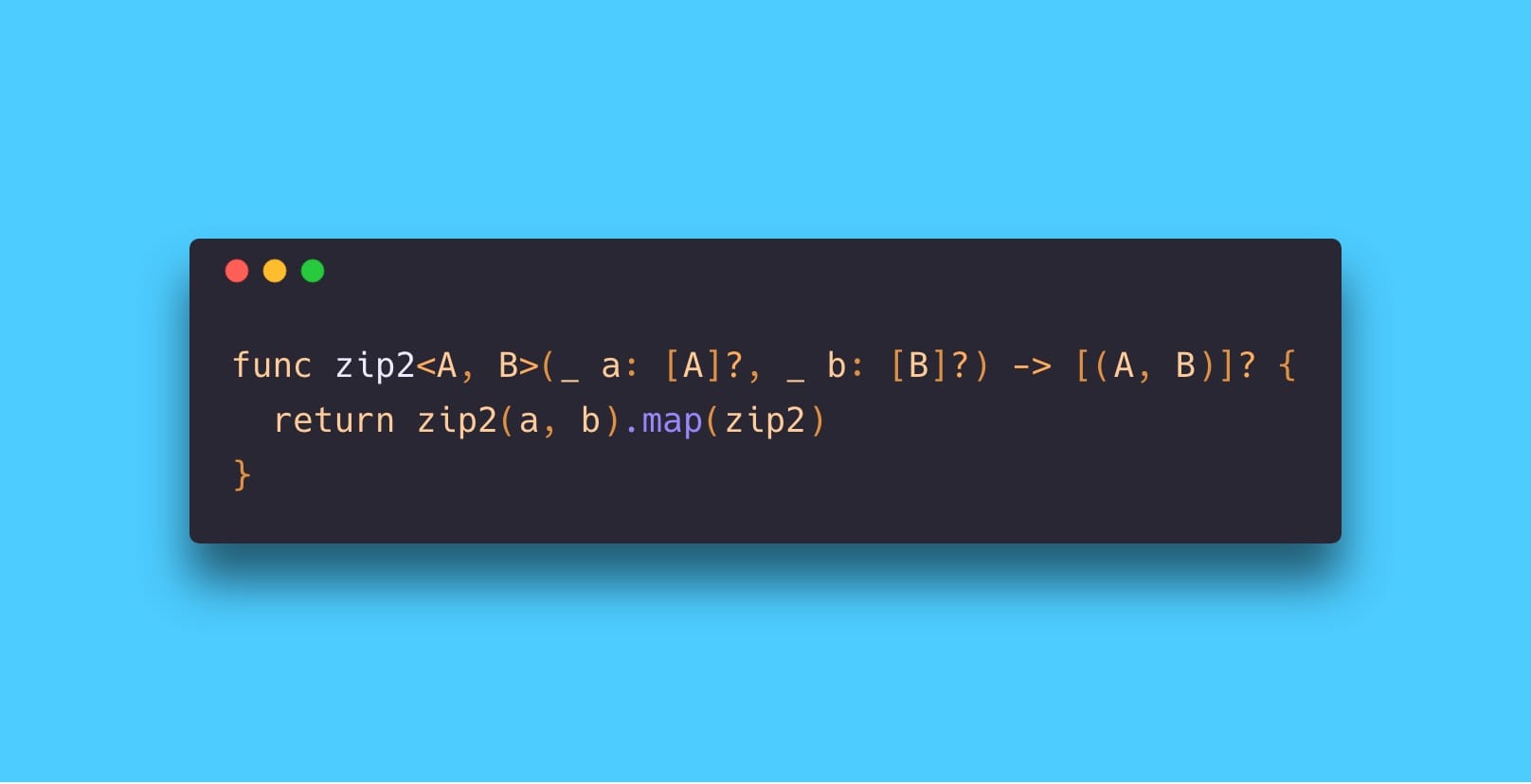

By mapping and then zipping we ended up with an optional array of tuples, which is precisely what we wanted since the return type is OptionalArray<(A, B)>. So, this is the implementation we were looking for, but let’s clean it up a bit by writing it in the point-free style:

func zip2<A, B>(

_ a: OptionalArray<A>, _ b: OptionalArray<B>

) -> OptionalArray<(A, B)> {

zip2(a, b).map(zip2)

}

Short and sweet! To zip a nested optional array you simply map on the zip of the optionals using the zip on arrays as the transformation function.

And that’s the solutions to the first part of our 3 part introductory series to zip! If you thought those were too easy, be sure to check out the exercises to part 2 and part 3 too. Until next time!